Uncategorized

-

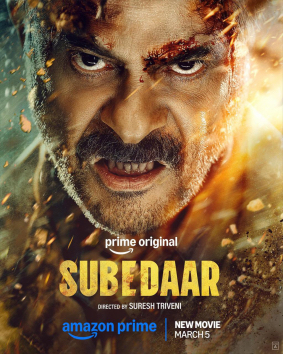

Full disclosure: I’ve just made a Netflix show with Anil Kapoor. Aditya Rawal plays Nibras in my film Faraaz and has an integral role in Gandhi. Neither fact disqualifies what follows. Both are forces of nature — and that is where any fair-minded review of Subedaar must begin. There is a phrase that keeps returning…

-

There are filmmakers whose work you admire, and then there are filmmakers whose work recognises you. Noah Baumbach belongs firmly in the latter category. Across two decades, his cinema has quietly but relentlessly built an interior landscape. One that charts the fault lines between love and ego, presence and absence, intimacy and self-absorption. Jay Kelly…

-

I first heard about Rivals when the International Emmys were announced a few weeks ago. A Disney/Hulu show, apparently. What surprised me more was that it had been available all this while on our very own JioHotstar. Quietly sitting there, unannounced, un-hyped, waiting to be discovered. So I watched. Then I read up a little.…

-

Some films arrive like a whisper. You don’t notice them at first. Then they settle inside you and refuse to move. Train Dreams is one of those films. Clint Bentley and Greg Kwedar’s adaptation of Denis Johnson’s novella is quiet and unhurried, almost deceptively simple, but somewhere along the way it opened a small window…

-

The death of a 26 year old PhD scholar at the Hyderabad University on 17th January 2016 disturbed me. Rohit Vemula’s death continues to disturb me very deeply. That someone so young should even contemplate suicide is disturbing enough. That he did commit suicide gives me sleepless nights even now. Was it cowardice? Was it despair?…

-

In 2014 I completed roughly 20 years in the industry – of course encompassing my work as a TV producer/director, editor and filmmaker (and atrocious makeshift actor at times). I call these 20 years my life. The remaining years were another life, led by another person, lived by another soul. In 1994 I was a…

-

Longing is punishment. Yearning is torture. Unleashed by forces. Beyond our control. Motivated by a concept. Called love. Fueled by a nuisance. Called lust. Controlled by a demon. Called passion. I yearn for you. Long to be with you. Dream about us. Remember what was. Imagine what could be. Unable to endure. What is. Without…